As part of Ropes & Gray’s Enforcement Express series, Patrick Doherty interviews Stéphane de Navacelle to discuss the current anti-corruption landscape in France and related legal considerations for businesses and individuals operating in the country.

Patrick Doherty: Welcome to our latest installment of On the Ropes: Enforcement Risk Roundtable, a Ropes & Gray podcast series focused on global anti-corruption and international risk. I’m Patrick Doherty, a litigation and enforcement associate based on London. Today, in our next stop on our Enforcement Express world tour, we’ll be exploring the current anti-corruption landscape in France, whose historical reputation for less aggressive enforcement has recently given way to a robust and proactive anti-corruption regime. To discuss, I’m joined today by Stéphane de Navacelle, managing partner at Navacelle in Paris. Bonjour, Stéphane. Before we dive in, would you mind giving a brief introduction?

Stéphane de Navacelle: First of all, thank you so much for having me. In a nutshell, I’ve been practicing white collar crime and investigations for over 15 years globally, moving the shift of these large investigations from the U.S. to Europe, working on a number of landmark matters here. I’ve taken on a number of assignments as independent investigator and monitor for private and public sector mandates. And as you mentioned, I’m now managing a Paris-based litigation/dispute firm. I’m always delighted to work with our friends at Ropes.

The enforcement landscape in France

PD: It sounds like we’re in good hands. To start off, can you walk us through, at a high-level, the enforcement landscape in France?

SN: We have the usual suspects—banking, financial markets, competition, regulator. Something that’s maybe not unusual to Europe but may be unusual to other jurisdictions is the Data Protection Agency, but also more specifically, two most recent creations. One is the National Financial Prosecutor, which addresses the more severe financial business crimes, and the Anti-Corruption Agency.

Now, as you mentioned, France has had a very bad reputation when it comes to enforcement, and it was very much considered a backbencher. They’ve come to realize that, especially after the number of large sanctions from U.S. enforcement authorities, and we’ve taken up our own FCPA/Bribery Act law, which is called “Sapin II,” in 2016 and it does a number of things.

The most radical change is that it imposes a compliance obligation for companies with more than 500 employees globally and an annual turnover of over 100 million Euros. What it does basically is this compliance obligation is monitored by one of the agencies I’ve just mentioned, the Anti-Corruption Agency (the AFA), and they can come and audit you at any time. They will evaluate your compliance system, they will provide a report, and they can refer you to a sanctions committee which can impose specific fines on individuals, on the company, and impose that you get your ducks in line, if you will, and have your own compliance program set up properly.

One last thing that this Anti-Corruption Agency does is it helps out with implementing monitorship programs once you have signed the equivalent of a DPA, which is a CJIP (“Convention judiciaire d’intérêt public”). One of the key concerns here when you have the AFA knocking at your door is that they are under a legal obligation as civil servants to report any crime they become aware of—any suspicion of crime. So, basically, having the AFA in your offices making requests you cannot dodge means that you have a prosecutor there, because they will be informed. And we have seen that repeatedly—the AFA informing the French National Financial Prosecutor (the PNF) of alleged bribery or anti-trust violations, and so on and so forth. So, they’re not your friends.

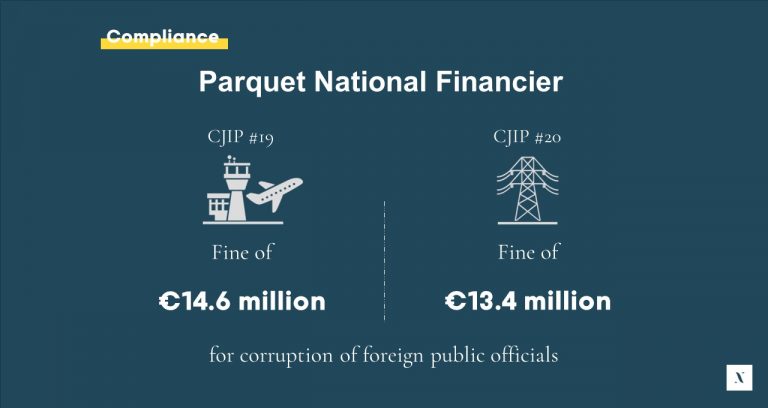

Convention judiciaire d’intérêt public (CJIP)

PD: You mentioned CJIPs in there—can you explain what those are a little more, and how France has been employing them, particularly since Sapin II was enacted?

SN: CJIPs are intellectual torture because, in France, we really love government, and so, we did not want to “compromise” with the criminal system. But it was a real politic answer to U.S. enforcement, and it was a real call to have the proper tools.

So, the PNF, it’s an agency of 20 prosecutors, and that seems maybe a lot for France, but it’s really very little when you think that they have ongoing over 600 open matters, and they focus on corruption, influence peddling, tax evasion, and the laundering of the above. Basically what the CJIP does is an opportunity to put an end to prosecution without admitting guilt, and the way it is entered into is through the usual discussions that you will have amongst outside counsel, the PNF, and the victims. If it’s a tax concern, you’ll be in discussions with the tax authorities, as well. If there’s a competition issue, you’ll be in discussion with the competition authority, and so on and so forth. So, there are many players that can come into play.

The key here is, of course, the amount of the fine and how it’s calculated, but whether there are identified or identifiable victims, because they will play a very big part in the process, as if you strike a deal with the prosecutor, you still need to get approved by a homologation judge. Now, I understand that, in the U.S. (for instance), the leeway of the judge reviewing the DPA is very weak. In France, we have developed case law that shows that the decision to homologate, that is to say, to approve the CJIP or the DPA, is not appealable. And so, you can find yourself in a terrible situation where you have admitted guilt as part of the contract that you’ve signed for the CJIP, but your CJIP is not homologated. Now, of course, all those documents are supposed to be set aside, but in these cases that are public, with a hearing in open court, it’s terrifying to think that you have to show up, due to stand trial, having accepted guilt.

PD: Do you anticipate that the PNF will be expanding any time in the near future?

SN: I don’t expect the PNF will be expanding beyond its 20-prosecutor figure or so. What is likely to happen is they will select their cases. In effect, we had a lead prosecutor who really cherry-picked her cases and pushed them forward. The current prosecutor is taking a more civil servant approach, and pushing them slowly forward. But what is expected is that will change because he has been highly criticized for not pushing forward a sufficient number of matters, and because of the slowness of the procedures.

There has been developing case law in 2021 in which we are expecting several Supreme Court decisions in 2022 which address the length of procedures, especially in white collar matters, and that will put a pressure on the PNF to move forward more efficiently.

Focus on international cooperation

PD: Now, in January 2020, France, the United Kingdom and the United States entered into the first-ever trilateral settlement agreement, which resulted in the largest global foreign bribery penalty in history. Toulouse-based Airbus agreed to pay more than 3.6 billion Euros to resolve charges stemming from its alleged use of third-party business partners to bribe government officials and airline executives around the world. More than 2 billion Euros of this settlement was paid to France as part of Airbus’s CJIP with the PNF. Can you talk a little bit about that and what that means for international cooperation, going forward?

SN: The Airbus case is quite an important matter for us in France because it’s a matter where we were not piggybacking U.S. enforcement, but the PNF worked hand in hand with the SFO (and the DOJ came in at a later time). What it did do, when it comes to the investigation, is there was a real coordination between the agencies and the internal investigations. So, depending on the type of business unit in which the individual that was to be interviewed was, it would be either the U.K. or the French. When it was not a key individual, then the internal investigation could interview that person. That was done in a way that was very specific in terms of reporting, taping the interviews, and so on and so forth.

There has been a lot of criticism of the PNF and of the lawyers carrying out the internal investigation because of the limited rights of people being called in for interviews while they were still employees of Airbus. It was groundbreaking in many different ways, and also because there was no possibility for the PNF to carry out this investigation in such a speedy way without really relying on the internal investigation. That is something that is new, but also puts an expectation on the companies to fix things and not just wait until the prosecution knocks at the door.

I should add here that there was an order, une circulaireyou say in French, which specifically instructs financial prosecutors all over France to transfer their matters when it comes to cross-border corruption, for instance, to the PNF so they make sure that the PNF concentrates all those matters, and a separate instruction that the financial prosecutors open their own investigation when they receive a request if there is material evidence that they may be a French competence.

So, if you have a foreign investigation and you think there is a French nexus or there is evidence that is going to be requested from France, you should definitely consider France as a jurisdiction to deal with, and the PNF potentially an enforcement authority to go and meet before it is contacted by a foreign authority.

Protections that French law provides the subjects of investigations

PD: One thing I found particularly interesting is the protections that French law provides the subjects of investigations. Can you talk a little bit about that?

SN: There are two issues here that I think maybe we can address as a matter of law.

One is the French Blocking Statute, which is basically an anti-discovery tool and has mutated into a reassessment-of-sovereignty tool, especially with Sapin II. What it does is it compels providing evidence of vast different substance, economic, industrial, financial and so on—it compels to go through treaties. The idea is that when you are contacted by a foreign authority and asked to provide documents or evidence, and so on and so forth, you should reach out to the SISSE, which is a department of the Financial Ministry. They will control the request—they will impose a review of the document production or they will put conditions on the giving of testimony. The idea is to raise awareness amongst French companies that enforcement can be used as a tool of “lawfare” instead of warfare, and that’s a great concern and one of the reasons why we had Sapin II in the first place.

The other issue is, of course, data privacy. There is a litigation exception, so it is not something that would block you in any way. That being said, it needs to be properly addressed, and when information is transferred, it should be done in a way that complies with the regulation, and it is strongly controlled by the French Data Privacy Agency.

Maybe a couple of other issues. One is the ethical rules for lawyers carrying out internal investigations: The right to counsel for the person interviewed, and counsel should be paid by the company. There have been a number of prosecutors expressing discontent with internal investigations, and so, if you have any reason to believe that there is ongoing criminal investigation or enforcement in any way, it is probably better to reach out to the authority to explain what you’re doing—not to ask for authorization, but to explain what you’re doing.

PD: In terms of the blocking statutes, how has that been received by other countries’ enforcement agencies? And as an extension of that, do you expect any changes to the blocking statutes in the near term?

SN: Generally speaking, my experience over the past six to 12 months is that foreign enforcement authorities have taken very little regard for the Blocking Statute, but more generally for treaties, and asking that people come for voluntary interviews and not send those requests through treaty requests as they should. My sense is authorities are going to, more and more, enter into direct contacts and emails, and especially when it comes to anything that they feel would impede their investigation.

The Blocking Statute, in itself, is not going to change, but the control by the SISSE is going to be enhanced. And the SISSE, which is this department from the Finance Ministry, has communicated in December that over the next few months, it will provide a system by which you can consult them, and they will answer and tell you whether you can or cannot answer a request by a foreign authority. So, that will make things much clearer for the clients, but it also will create potential frustration because foreign authorities, as you suggest in your question, may be unhappy with anything that prevents them from moving forward swiftly.

Developments for 2022 on anti-corruption and international risk perspectives

PD: Thanks, Stéphane—this has all been incredibly helpful. Before we sign off, having just begun a new year, are there any trends or developments that you’re keeping an eye on for 2022?

SN: Three main trends. One is we’re likely to have a new anti-corruption law, an updated anti-corruption law, that will target more specifically lobbying, and put a framework on lobbying and how money is spent, and avoid that loophole. Another one is going to be a real battle over privilege. Privilege has come under considerable pressure—the rules on privilege changed in December 2021, and I expect that will be litigated in court. And the last major issue is the European prosecutor, which was set up last summer, that has now a real team and will provide healthy competition with the PNF. So, if the French branch of the European prosecutor moves forward swiftly, the PNF will want to do the same, and so that will, I think, incentivize everyone to want to move forward with their matters.

PD: Thanks, Stéphane—that was a wonderful discussion. Thank you for joining us and sharing your thoughts. And thank you, once more, to our listeners.