Arbitration law has once again given rise to a wealth of case law over the past year. Navacelle has selected a number of decisions dealing specifically with the treatment of allegations of fraud and corruption at the review stage, as well as with the implementation of international sanctions in the context of award enforcement.

I. A party who, without legitimate reason, refrains from raising in due course grounds relating to a certain type of alleged fraud in the formation and performance of the contract, which is the subject of the dispute, is presumed to have waived its right to rely thereon

In order to prevent a party from reserving arguments to slow down the arbitration proceedings, or to have the resulting award set aside if the outcome of the arbitration is unfavorable to this party, belated arguments are generally ruled inadmissible. By way of exception, certain arguments, even when raised later, remain admissible, as they are designed to protect certain interests that are often referred to as “superior”. This applies, for example, to corruption. An award can always be annulled on the grounds that its upholding would enable one to benefit from corruption. This holds true even when the alleged corruption has not been mentioned beforehand, particularly during the arbitration.

However, defining which arguments do and do not fall within the scope of this exception is quite a challenge.

In a ruling handed down on 21 January 2025 (No. 23/05511), the Paris Court of Appeal addressed this issue and provided some interesting clarifications.

The Court ruled on a challenge to an arbitration award rendered on 26 February 2023 in a dispute between the Central Bank of Iraq (“CBI”) and Cardno Middle East Limited (“Cardno”).[1] The dispute that gave rise to this award related to the performance of a consultancy contract for the construction of the CBI’s new headquarters in Baghdad.[2] Following defaults to its payment obligations by the CBI, Cardno initiated arbitration proceedings administered by the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) and seated in Paris, thereby rendering French international arbitration law applicable to the arbitration.[3] The arbitral tribunal, composed of a sole arbitrator, ordered the CBI to, inter alia, pay Cardno the amount of unpaid invoices and damages.[4]

The CBI filed an application to set aside the award, arguing in particular that the recognition of the award would constitute a breach of international public policy in that it would allow Cardno to benefit from the proceeds of criminal acts and fraud, and that the award was vitiated by procedural fraud.[5] More specifically, the CBI alleged that Cardno had obtained the consultancy contract fraudulently – by concealing its lack of experience and its non-affiliation with a well-known company, Cardno International – and that the performance of the contract was also tainted by fraud – in particular by invoicing fictitious services.[6] In reply, Cardno argued that this argument was inadmissible, on the basis of Article 1466 of the French Code of Civil Procedure, which provides that a party who fails to raise an irregularity before the arbitral tribunal in due time is deemed to have waived its right to rely on it.[7] According to Cardno, the CBI had not raised this argument in due course before the arbitrator, and nothing prevented it from doing so.[8]

As stated above, Article 1466 of the French Code of Civil Procedure is subject to exceptions. Thus, Cardno relied on the distinction between substantive public policy, which the parties cannot dispose of, and protective public policy, which the parties can waive.[9] In so doing, Cardno hoped that the judge would make a distinction between various types of fraud, those that must be raised in due time to be admissible and those that must not.

In the present case, the Court finds that, while the allegations related to facts presented as fraudulent by the CBI – characterized by the CBI as embezzlement of public funds, embezzlement, forgery, money laundering and identity theft and which could be characterized as offences under Iraqi law[10] –, they primarily related to acts affecting the formation or performance of the underlying contract and private interests, and therefore did not fall within the scope of international public policy. [11] A distinction is thus made between the facts of the case, which concern private interests, and the issues of fraud and money laundering in public matters, which are more traditionally considered to fall within the scope of international public policy. In particular, and in order to distinguish between “legal and factual grounds freely at [the CBI’s] disposal”, and what would fall within the scope of international public policy, the Court ruled that there was no mention of corruption of public officials, and that the alleged misappropriation of funds concerned the administration of the CBI’s private interests, and was the work of a private operator.[12]

The Court thus attempts to restrict the scope of international public policy by limiting it to the protection of purely public interests.

Noting that the CBI had prior knowledge of the alleged grievances and that it had been able to put forward its position during the arbitration proceedings, the Court found that it had waived its right to rely on this ground, which it ruled inadmissible.[13].

This judgment provides interesting clarifications as to what constitutes a principle of international public policy in the context of allegations of fraud. If the conclusion was not totally convincing to some authors[14], the court distinguished between public and private interests. Finally, it should be noted that the debate is not over, as the Cour de cassation will probably be called upon to examine these questions.

II. The scope of the international sanctions regimes at issue in the case of payment under an international award

As a central instrument of foreign policy and international relations, international sanctions inherently have effects in private law and consequences on international trade.[15] For example, the prohibition on importing Russian oil obviously affects any person subject to this ban who previously sourced its oil from Russian producers under long-term contracts. Such a person must suspend the performance of any contracts with these suppliers and may face judicial or arbitral proceedings for breach of contract.

It is therefore unsurprising to see sanctions invoked in the context of arbitration proceedings or the enforcement of arbitral awards. The tension between the public and private nature of these instruments has been the subject of recent jurisprudential developments, of which this judgment constitutes a new milestone.

In the case at hand, the Cour de cassation heard a challenge lodged against a decision handed down by the Court of Appeal of Paris in a dispute between the companies DNO Yemen, Petrolin Trading, and MOE Oil & Gas Yemen (“MOE”) and the State of Yemen and the public company Yemen Oil & Gas Corporation (“YOGC”), within the framework of an oil and gas project in Yemen.[16] Following disagreements in the performance of the contracts, the State parties initiated arbitration proceedings which resulted in the DNO Yemen, Petrolin Trading, and MOE being found liable.[17] The latter filed an application to set aside the award, arguing that the award would indirectly benefit entities subject to international sanctions, notably Regulation (EU) No. 1352/2014 of 18 December 2014, which, in its version of 8 June 2015, provided in Article 2.2 that “no funds or economic resources shall be made directly or indirectly available to natural or legal persons, entities, or bodies listed in Annex I [which at that time included a number of Houthi dignitaries and commanders], or used for their benefit.”

In its decision dated 5 October 2021, the Court of Appeal of Paris examined in detail the scope of these sanctions to determine whether, at the time of its decision and based on “serious, precise, and consistent” evidence, the recognition or enforcement of the award was likely to violate the sanctions by providing assets directly or indirectly to persons or entities listed under the sanctions. It thus determined that the Ministry of Oil and Minerals of the Republic of Yemen and YOGC were not subject to the sanctions and dismissed the setting-aside application.[18]

In support of their appeal, the appellants criticized the Court of Appeal for dismissing their challenge by limiting the scope of Article 2.2 of Regulation (EU) No. 1352/2014. In particular, they stated that the Court of Appeal failed to investigate whether the beneficiaries of the award intended to make the damages and interest obtained available to sanctioned persons; regardless that the latter do not exercise control over or instruct the beneficiaries of the award. In other words, they blamed the Court of Appeal for applying an incorrect analytical framework.[19]

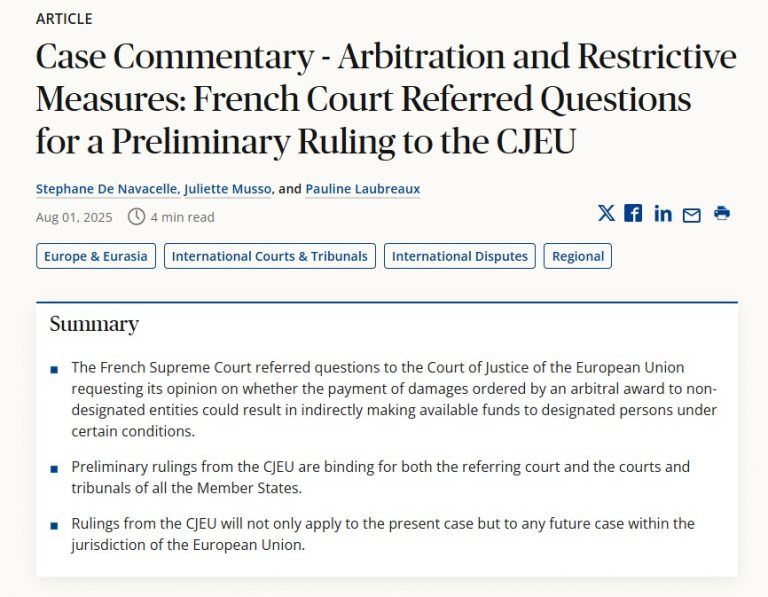

On this question, the Cour de cassation, faced with the interpretation of European Union law, decided to stay proceedings and request a preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”). It notably asked the CJEU about the scope of the notion of “indirectly making available” funds in the case of a payment made in enforcement of an arbitral award benefiting an entity over which “competing influence” is exercised, both by legitimate parties and parties targeted by the sanctions.[20] The Court also asked the CJEU about the presumption of control and the standard to be applied in this case.[21]

This judgment by the Cour de cassation fits within this trend and should help to more precisely define the role of the supervisory judge and the scope of international sanctions.

In a string of recent decisions[22], French courts have engaged in examining the scope of international sanctions in the recognition or enforcement of arbitral awards. This judgment by the Cour de cassation fits within this trend and should help to more precisely define the role of the supervisory judge and the scope of international sanctions. Moreover, the question of the appropriate sanction in case of non-compliance with international public policy may arise in this context. Indeed, is the annulment of an arbitral award – which has a definitive effect – proportionate, whereas the international sanction is, by definition, intended to be temporary? It has thus been suggested that refusal of recognition, being more flexible and reversible, could constitute a more suitable alternative.[23]

III. The recognition of an award does not violate international public policy in the absence of serious, precise, and consistent indications of corruption

In a judgment dated 17 September 2024, the Court of Appeal of Paris once again examined allegations of corruption affecting the contracts that were the subject of the arbitral award. This decision, which forms part of an increasingly well-established body of case law, serves as a reminder of the principles governing the review of an award in the context of corruption allegations.

The dispute related to the enforcement of a settlement agreement intended to amicably resolve a disagreement over a contract for the supply and operation of a telecommunications traffic monitoring platform between the Republic of Chad and the company N-Soft Ltd (“N-Soft”).[24] The settlement agreement provided for the termination of the contract and the payment by Chad of an amount of 25 million euros to N-Soft.[25] In the absence of payment, N-Soft initiated arbitration proceedings under the rules of the Common Court of Justice and Arbitration (“CCJA”), with the seat of arbitration in Abidjan. The award rendered on 23 May 2022 ordered Chad to pay, in particular, the 25 million euros owed under the settlement agreement.[26]

To challenge the enforcement of the award in France, Chad invoked a violation of international public policy, alleging acts of corruption that had tainted the conclusion of both the supply and operation contract and the settlement agreement. More specifically, Chad alleged that, in connection with the conclusion of the contract, commissions had been paid to public officials for services whose existence had not been established.[27] It also alleged, with regard to the settlement agreement, the absence of negotiation, disproportionate consideration, and its signing by a minister who was not authorized to do so.[28]

The Court, in line with its established case law on the subject, first recalled that its review focuses on ensuring that the incorporation of the award into the French legal order must not have the effect of giving force to a contract obtained by corruption or allowing a party to benefit from the proceeds of such corruption. To do so, the Court sought to identify serious, precise, and consistent evidence.[29] It further added that this evidentiary inquiry was not limited to the elements presented within the arbitral proceedings.[30] Accordingly, the Court conducted a detailed factual analysis. In this regard, and as explained above in the Cardno case, it did not matter that the allegations of corruption were not raised before the arbitrator since this concerns international public policy.

The Court first examined the allegations of corruption surrounding the execution of the contract, noting that while it appears intermediaries were paid by N-Soft, Chad failed to provide proof that these intermediaries were public officials.[31] The Court also noted that the remuneration of these intermediaries, although seemingly high, was not without consideration.[32] Finally, the court relied on a dismissal order issued in the context of proceedings in Chad, which exonerates the intermediaries.[33]

The Court then examined the settlement agreement, noting first of all that its terms were the subject of negotiations between the parties.[34] The Court examined the contractual balance of the settlement agreement and its underlying rationale, concluding that it is not devoid of any “egal or economic justification, nor does it go against [Chad’s] interests.”[35]. Finally, the Court noted that the validity of the settlement agreement has not been challenged, so that its irregular signing is insufficient to indicate that it is tainted by corruption.[36]

The Court concluded that “the evidence of a set of serious, precise, and consistent indications of acts of corruption […] has not been established.”[37], demonstrating a certain strictness in the level of proof required regarding allegations of corruption intended to prevent the enforcement of an arbitral award in France.